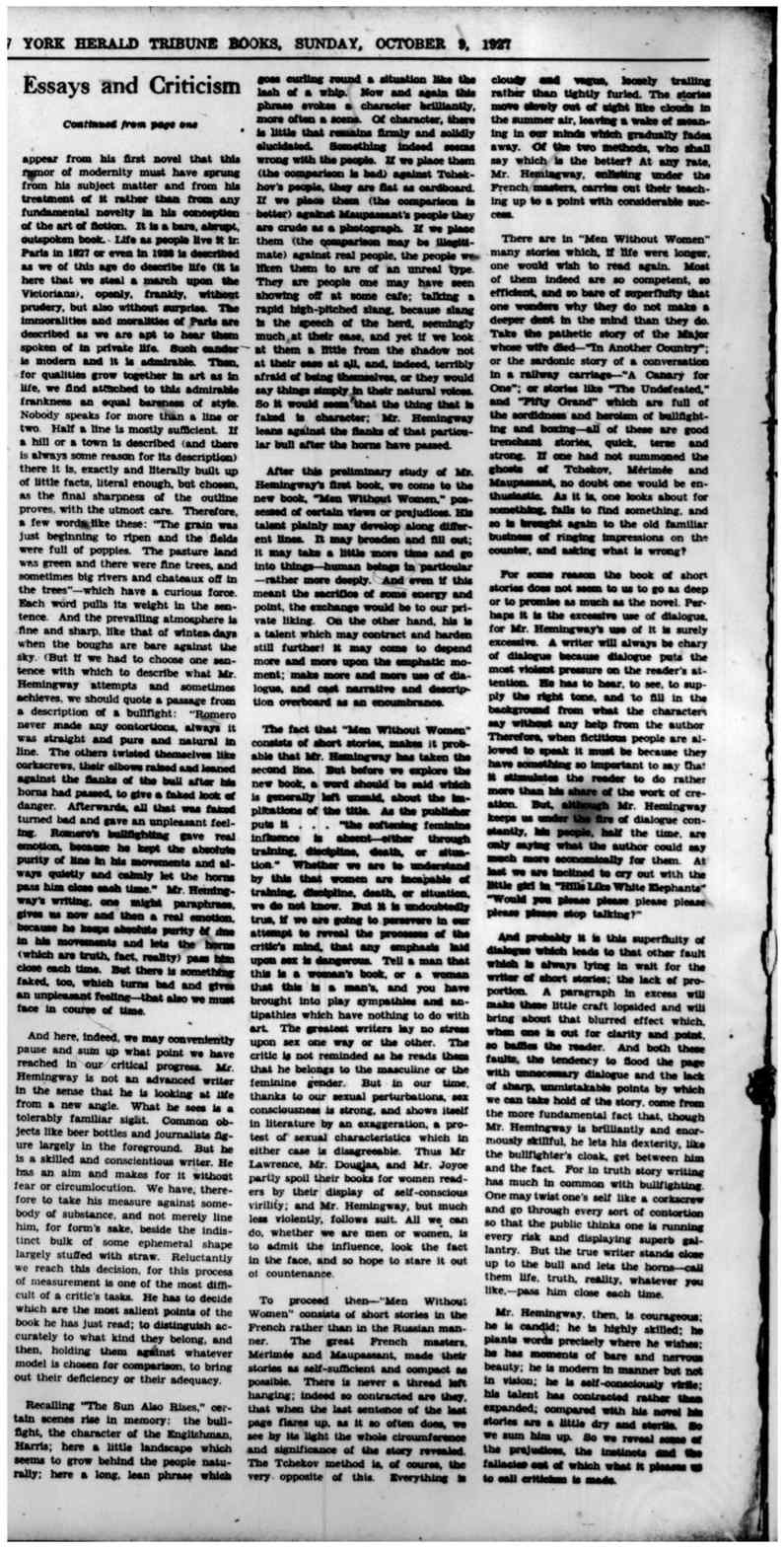

[new page]

appear from his first novel that this

rumor of modernity must have sprung

from his subject matter and from his

treatment of it rather than from any

fundamental novelty in his conception

of the art of fiction. It is a bare, abrupt,

outspoken book. Life as people live it in

Paris in 1927 or even in 1928 is described

as we of this age do describe life (it is

here that we steal a march upon the

Victorians), openly, frankly, without

prudery, but also without surprise. The

immoralities and moralities of Paris are

described as we are apt to hear them

spoken of in private life. Such candor

is modern and it is admirable. Then,

for qualities grow together in art as in

life, we find attached to this admirable

frankness an equal bareness of style.

Nobody speaks for more than a line or

two. Half a line is mostly sufficient. If

a hill or a town is described (and there

is always some reason for its description)

there it is, exactly and literally built up

of little facts, literal enough, but chosen,

as the final sharpness of the outline

proves, with the utmost care. Therefore,

a few words like these: “The grain was

just beginning to ripen and the fields

were full of poppies. The pasture land

was green and there were fine trees, and

sometimes big rivers and chateaux off in

the trees”—which have a curious force.

Each word pulls its weight in the sen-

tence. And the prevailing atmosphere is

fine and sharp, like that of winter days

when the boughs are bare against the

sky. (But if we had to choose one sen-

tence with which to describe what Mr.

Hemingway attempts and sometimes

achieves, we should quote a passage from

a description of a bullfight: “Romero

never made any contortions, always it

was straight and pure and natural in

line. The others twisted themselves like

corkscrews, their elbows raised and leaned

against the flanks of the bull after his

horns had passed, to give a faked look of

danger. Afterwards, all that was faked

turned bad and gave an unpleasant feel-

ing. Romero's bullfighting gave real

emotion, because he kept the absolute

purity of line in his movements and al-

ways quietly and calmly let the horns

pass him close each time.”) Mr. Heming-

way's writing, one might paraphrase,

gives us now and then a real emotion,

because he keeps absolute purity of line

in his movements and lets the horns

(which are truth, fact, reality) pass him

close each time. But there is something

faked, too, which turns bad and gives

an unpleasant feeling—that also we must

face in course of time.

And here, indeed, we may conveniently

pause and sum up what point we have

reached in our critical progress. Mr.

Hemingway is not an advanced writer

in the sense that he is looking at life

from a new angle. What he sees is a

tolerably familiar sight. Common ob-

jects like beer bottles and journalists fig-

ure largely in the foreground. But he

is a skilled and conscientious writer. He

has an aim and makes for it without

fear or circumlocution. We have, there-

fore to take his measure against some-

body of substance, and not merely line

him, for form's sake, beside the indis-

tinct bulk of some ephemeral shape

largely stuffed with straw. Reluctantly

we reach this decision, for this process

of measurement is one of the most diffi-

cult of a critic's tasks. He has to decide

which are the most salient points of the

book he has just read; to distinguish ac-

curately to what kind they belong, and

then, holding them against whatever

model is chosen for comparison, to bring

out their deficiency or their adequacy.

Recalling “The Sun Also Rises,” cer-

tain scenes rise in memory: the bull-

fight, the character of the Englishman,

Harris; here a little landscape which

seems to grow behind the people natu-

rally; here a long, lean phrase which

[new column]

goes curling round a situation like the

lash of a whip. Now and again this

phrase evokes a character brilliantly,

more often a scene. Of character, there

is little that remains firmly and solidly

elucidated. Something indeed seems

wrong with the people. If we place them

(the comparison is bad) against Tchek-

ov's people, they are flat as cardboard.

If we place them (the comparison is

better) against Maupassant's people they

are crude as a photograph. If we place

them (the comparison may be illegiti-

mate) against real people, the people we

liken them to are of an unreal type.

They are people one may have seen

showing off at some cafe; talking a

rapid high-pitched slang, because slang

is the speech of the herd, seemingly

much at their ease, and yet if we look

at them a little from the shadow not

at their ease at all, and, indeed, terribly

afraid of being themselves, or they would

say things simply in their natural voices.

So it would seem that the thing that is

faked is character; Mr. Hemingway

leans against the flanks of that particu-

lar bull after the horns have passed.

After this preliminary study of Mr.

Hemingway's first book, we come to the

new book, “Men Without Women,” pos-

sessed of certain views or prejudices. His

talent plainly may develop along differ-

ent lines. It may broaden and fill out;

it may take a little more time and go

into things—human beings in particular

—rather more deeply. And even if this

meant the sacrifice of some energy and

point, the exchange would be to our pri-

vate liking. On the other hand, his is

a talent which may contract and harden

still further! It may come to depend

more and more upon the emphatic mo-

ment; make more and more use of dia-

logue, and cast narrative and descript-

tion overboard as an encumbrance.

The fact that “Men Without Women”

consists of short stories, makes it prob-

able that Mr. Hemingway has taken the

second line. But before we explore the

new book, a word should be said which

is generally left unsaid, about the im-

plications of the title. As the publisher

puts it . . . “the softening feminine

influence is absent—either through

training, discipline, death, or situa-

tion.” Whether we are to understand

by this that women are incapable of

training, discipline, death, or situation,

we do not know. But it is undoubtedly

true, if we are going to persevere in our

attempt to reveal the processes of the

critic's mind, that any emphasis laid

upon sex is dangerous. Tell a man that

this is a woman's book, or a woman

that this is a man's, and you have

brought into play sympathies and an-

tipathies which have nothing to do with

art. The greatest writers lay no stress

upon sex one way or the other. The

critic is not reminded as he reads them

that he belongs to the masculine or the

feminine gender. But in our time,

thanks to our sexual perturbations, sex

consciousness is strong, and shows itself

in literature by an exaggeration, a pro-

test of sexual characteristics which in

either case is disagreeable. Thus Mr.

Lawrence, Mr. Douglas, and Mr. Joyce

partly spoil their books for women read-

ers by their display of self-conscious

virility; and Mr. Hemingway, but much

less violently, follows suit. All we can

do, whether we are men or women, is

to admit the influence, look the fact

in the face, and so hope to stare it out

of countenance.

To proceed then—“Men Without

Women” consists of short stories in the

French rather than in the Russian man-

ner. The great French masters,

Mérimée and Maupassant, made their

stories as self-sufficient and compact as

possible. There is never a thread left

hanging; indeed so contracted are they,

that when the last sentence of the last

page flares up, as it so often does, we

see by its light the whole circumference

and significance of the story revealed.

The Tchekov method is, of course, the

very opposite of this. Everything is

[new column]

cloudy and vague, loosely trailing

rather than tightly furled. The stories

move slowly out of sight like clouds in

the summer air, leaving a wake of mean-

ing in our minds which gradually fades

away. Of the two methods, who shall

say which is the better? At any rate,

Mr. Hemingway, enlisting under the

French masters, carries out their teach-

ing up to a point with considerable success.

There are in “Men Without Women”

many stories which, if life were longer,

one would wish to read again. Most

of them indeed are so competent, so

efficient, and so bare of superfluity that

one wonders why they do not make a

deeper dent in the mind than they do.

Take the pathetic story of the Major

whose wife died—“In Another Country”;

or the sardonic story of a conversation

in a railway carriage—“A Canary for

One”; or stories like “The Undefeated,”

and “Fifty Grand” which are full of

the sordidness and heroism of bullfight-

ing and boxing—all of these are good

trenchant stories, quick, terse and

strong. If one had not summoned the

ghosts of Tchekov, Mérimée, and

Maupassant, no doubt one would be en-

thusiastic. As it is, one looks about for

something, fails to find something, and

so is brought again to the old familiar

business of ringing impressions on the

counter, and asking what is wrong?

For some reason the book of short

stories does not seem to us to go as deep

or to promise as much as the novel. Per-

haps it is the excessive use of dialogue,

for Mr. Hemingway's use of it is surely

excessive. A writer will always be chary

of dialogue because dialogue puts the

most violent pressure upon the reader's at-

tention. He has to hear, to see, to sup-

ply the right tone, and to fill in the

background from what the characters

say without any help from the author.

Therefore, when fictitious people are al-

lowed to speak it must be because they

have something so important to say that

it stimulates the reader to do rather

more than his share of the work of cre-

ation. But, although Mr. Hemingway

keeps us under the fire of dialogue con-

stantly, his people, half the time, are

only saying what the author could say

much more economically for them. At

last we are inclined to cry out with the

little girl in “Hills Like White Elephants”

“Would you please please please please

please please stop talking?”

And probably it is this superfluity of

dialogue which leads to that other fault

which is always lying in wait for the

writer of short stories; the lack of pro-

portion. A paragraph in excess will

make these little craft lopsided and will

bring about that blurred effect which,

when one is out for clarity and point,

so baffles the reader. And both these

faults, the tendency to flood the page

with unnecessary dialogue and the lack

of sharp, unmistakable points by which

we can take hold of the story, come from

the more fundamental fact that, though

Mr. Hemingway is brilliantly and enor-

mously skillful, he lets his dexterity, like

the bullfighter's cloak, get between him

and the fact. For in truth story writing

has much in common with bullfighting.

One may twist one's self like a corkscrew

and go through every sort of contortion

so that the public thinks one is running

every risk and displaying superb gal-

lantry. But the true writer stands close

up to the bull and lets the horns—call

them life, truth, reality, whatever you

like,—pass him close each time.

Mr. Hemingway, then, is courageous;

he is candid; he is highly skilled; he

plants words precisely where he wishes;

he has moments of bare and nervous

beauty; he is modern in manner but not

in vision; he is self-consciously virile;

his talent has contracted rather than

expanded; compared with his novel his

stories are a little dry and sterile. So

we sum him up. So we reveal some of

the prejudices, the instincts and the

fallacies out of which what it pleases us

to call criticism is made.