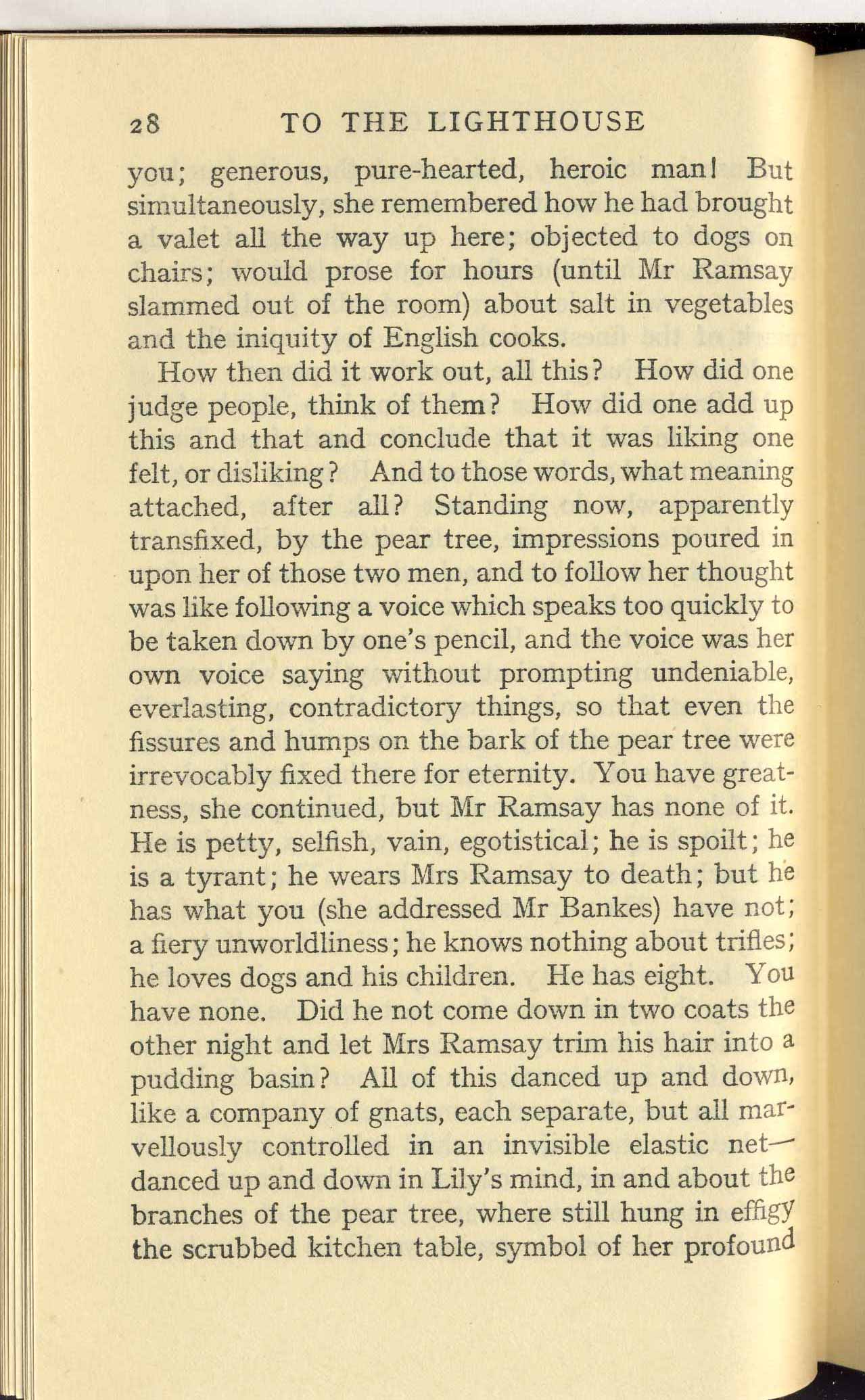

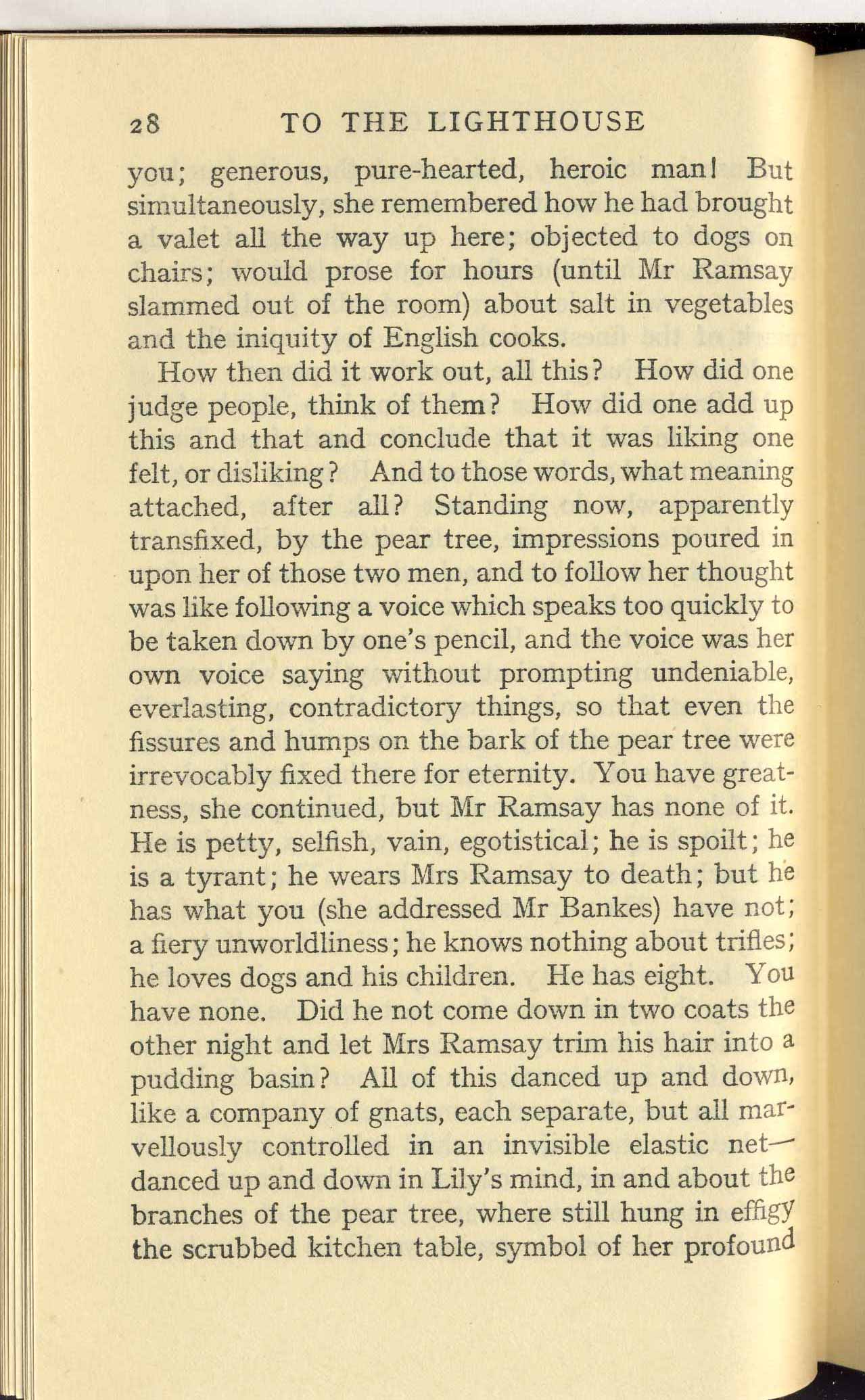

How then did it work out, all this? How did onejudge people, think of them? How did one add upthis and that and conclude that it was liking onefelt, or disliking? And to those words, what meaningattached, after all? Standing now, apparentlytransfixed, by the pear tree, impressions poured inupon her of those two men, and to follow her thoughtwas like following a voice which speaks too quickly tobe taken down by one’s pencil, and the voice was herown voice saying without prompting undeniable,everlasting, contradictory things, so that even thefissures and humps on the bark of the pear tree wereirrevocably fixed there for eternity. You have great-ness, she continued, but Mr Ramsay has none of it.He is petty, selfish, vain, egotistical; he is spoilt; heis a tyrant; he wears Mrs Ramsay to death; but hehas what you (she addressed Mr Bankes) have not;a fiery unworldliness; he knows nothing about trifles;he loves dogs and his children. He has eight. Youhave none. Did he not come down in two coats theother night and let Mrs Ramsay trim his hair into apudding basin? All of this danced up and down,like a company of gnats, each separate, but all mar-vellously controlled in an invisible elastic net—danced up and down in Lily's mind, in and about thebranches of the pear tree, where still hung in effigythe scrubbed kitchen table, symbol of her profound

Select Pane

Berg Materials

- 1. Notebook I Cover

- 2. F3 / P1

- 3. F5 / P2

- 4. F7 / P3

- 5. F9 / P4

- 6. F11 / P5

- 7. F13 / P6

- 8. F15 / P7

- 9. F17 / P8

- 10. F19 / P9

- 11. F21 / P10

- 12. F23 / P11

- 13. F25 / P12

- 14. verso of Berg F25

- 15. F27 / P13

- 16. F29 / P14

- 17. F31; P15

- 18. F33 / P16

- 19. F35 / P17

- 20. F37 / P18

- 21. F39 / P19

- 22. F41 / P20

- 23. F43 / P21

- 24. F45 / P22

- 25. F47 / P23

- 26. F49 / P24

- 27. F51 / P25

- 28. F53 / P26

- 29. F55 / P27

- 30. F57 / P28

- 31. F59 / P29

- 32. F61 / P30

- 33. F61 / P30 verso

- 34. F63 / P31

- 35. F65 / P32

- 36. F67 / P33

- 37. F69 / P34

- 38. F71 / P35

- 39. verso F71

- 40. F73 / P36

- 41. F75 / P37

- 42. F77 / P38

- 43. F79 / P39

- 44. F81 / P40

- 45. F91 / P45

- 46. F93 / P46

- 47. F95 / P47

- 48. F97 / P48

- 49. F99 / P49

- 50. F101 / P50

- 51. F103 / P51

- 52. F105 / P52

- 53. F107 / P53

- 54. F109 / P54

- 55. F111 / P55

- 56. F113 / P56

- 57. F115 / P57

- 58. F117 / P58

- 59. F119 / P59

- 60. verso F119

- 61. F121 / P60

- 62. F123 / P61

- 63. F125 / P62

- 64. F127 / P63

- 65. F129 / P64

- 66. F131 / P65

- 67. F133 / P66

- 68. F135 / P67

- 69. F137 / P68

- 70. F139 / P69

- 71. F139 / P69 verso

- 72. F141 / P70

- 73. F143 / P71

- 74. F145 / P72

- 75. F147 / P73

- 76. Fol. 149 / P74

- 77. F151 / P75

- 78. F153 / P76

- 79. F155 / P77

- 80. F157 / P78

- 81. F159 / P79

- 82. F161 / P80

- 83. F163 / P81

- 84. F167 / P82

- 85. 167 / P82 verso

- 86. F169 / P83

- 87. F171 / P84

- 88. F173 / P85

- 89. F175 / P86

- 90. F177 / P87

- 91. F179 / P88

- 92. F181 / P89

- 93. F183 / P90

- 94. F185 / P91

- 95. F187 / P92

- 96. F189 / P93

- 97. F191 / P94

- 98. F193 / P95

- 99. F195 / P96

- 100. F197 / P97

- 101. F197 / P97 verso

- 102. F199 / P98

- 103. F199 / P98 verso

- 104. F201 / P99

- 105. F203 / P100

- 106. F205 / P101

- 107. F207 / P102

- 108. F207 / 102 verso

- 109. F209 / P103

- 110. F211 / P104

- 111. F213 / P105

- 112. F215 / P106

- 113. F217 / P107

- 114. F219 / P108

- 115. F221 / P109

- 116. F223 / P110

- 117. F225 / P111

- 118. F227 / P112

- 119. F229 / P113

- 120. F231 / P114

- 121. F233 / P115

- 122. F235 / P116

- 123. F237 / P117

- 124. F239 / P118

- 125. F241 / P119

- 126. F243 / P120

- 127. F245 / P121

- 128. F247 / P122

- 129. F249 / P123

- 130. F251 / P124

- 131. F251 / P124 verso

- 132. F253 / P125

- 133. F255 / P126

- 134. F257 / P127

- 135. F259 / P128

- 136. F261 / P129

- 137. F263 / P130

- 138. F265 / P131

- 139. F267 / P132

- 140. F269 / P133

- 141. F271 / P134

- 142. F273 / P135

- 143. F275 / P136

- 144. F277 / P137

- 145. F279 / P138

- 146. F281 / P139

- 147. F283 / P140

- 148. F285 / P141

- 149. F287 / P142

- 150. F289 / P143

- 151. F291 / P144

- 152. F293 / P145

- 153. F295 / P146

- 154. F297 / P147

- 155. F299 / P148

- 156. F301 / P149

- 157. F303 / P150

- 158. F305 / P151

- 159. F307 / P152

- 160. F309 / P153

- 161. F311/ P154

- 162. F313 / P155

- 163. 156 verso

- 164. 157 verso

- 165. 158 verso

- 166. Notebook I Rear Cover

- 167. Notebook II Cover

- 168. N2F1 / P159

- 169. N2F3 / P160

- 170. N2F5 / P161

- 171. N2F7 / P162

- 172. N2F9 / P163

- 173. N2F11 / P164

- 174. N2F13 / P165

- 175. N2F15 / P166

- 176. N2F17 / P167

- 177. N2F19 / P168

- 178. N2F21 / P169

- 179. N2F23 / P170

- 180. N2F25 / P171

- 181. N2F27 /P172

- 182. N2F29 / P173

- 183. N2F31 / P174

- 184. N2F33 / P175

- 185. N2F35 / P176

- 186. N2F37 / P177

- 187. N2F39 / P178

- 188. N2F41 / P179

- 189. N2F43 / P180

- 190. N2F45 / P181

- 191. N2F47 / P182

- 192. N2F49 / P183

- 193. N2F51 / P184

- 194. Notebook II Rear Cover

- 195. Notebook III Cover

- 196. N3F1 / P185

- 197. N3F[3] / F138 / P186

- 198. N3F5 / F139 / P187

- 199. N3F7 / F140 / P188

- 200. N3F9 / F141 / P189

- 201. N3F11 / F142 / P190

- 202. N3F13 / F142 / P191

- 203. N3F15 / F143 / P192

- 204. N3F17 / F144 / P193

- 205. N3F19 / F145 / P194

- 206. N3F21 / F146 / P195

- 207. N3F23 / F147 / P196

- 208. N3F25 / F148 / P197

- 209. N3F27 / F149 / P198

- 210. N3F29 / F150 / P199

- 211. N3F31 / F151 / P200

- 212. N3F33 / F152 / P201

- 213. N3F35 / F153 / P202

- 214. N3F37 / F154 / P203

- 215. N3F39 / F155 / P204

- 216. N3F41 / F156 / P205

- 217. verso of VW P156

- 218. N3F43 / F157 / P206

- 219. N3F45 / F158 / P207

- 220. N3F47 / F159 / P208

- 221. N3F49 / F160 / P209

- 222. N3F51 / F161 / P210

- 223. N3F53 / F162 / P211

- 224. N3F55 / F163 / P212

- 225. N3F57 / F164 / P213

- 226. N3F59 / F165 / P214

- 227. N3F61/ F166 / P215

- 228. N3F63 / F167 / P216

- 229. F63 / P216 verso

- 230. NF65 / F168 / P217

- 231. N3F67 / F169 / P218

- 232. N3F69 / F170 / P219

- 233. 219 verso

- 234. N3F71 / F171 / P220

- 235. N3F73 / F172 / P221

- 236. N3F75 / F173 / P222

- 237. N3F77 / F174 / P223

- 238. N3F79 / F175 / P224

- 239. N3F81 / F176 / P225

- 240. 225 verso

- 241. N3F83 / F177 / P226

- 242. N3F85 / F178 / P227

- 243. N3F87 / F179 / P228

- 244. N3F89 / F180 / P229

- 245. 229 verso

- 246. N3F91 / F181 / P230

- 247. N3F93 / F182 / P231

- 248. N3F95 / F183 / P232

- 249. N3F97 / F184 / P233

- 250. F99 / P234

- 251. N3F101 / F185 / P235

- 252. N3F103 / F186 / P236

- 253. N3F105 / F187 / P237

- 254. N3F107 / F188 / P238

- 255. N3F109 / F189 / P239

- 256. N3F111 / F190 / P240

- 257. N3F113 / F191 / P241

- 258. N3F115 / F192 / P242

- 259. N3F117 / F193 / P243

- 260. N3F119 / F194 / P244

- 261. N3F121 / F195 / P245

- 262. N3F123 / F196 / P246

- 263. N3F125 / F197 / P247

- 264. N3F127 / F198 / P248

- 265. N3F129 / F199 / P249

- 266. N3F131 / F200 / P250

- 267. N3F133 / F202 / P251

- 268. NF135 / F203 / P252

- 269. N3F137 / F204 / P253

- 270. N3F139 / F205 / P254

- 271. N3F141 / F206 / P255

- 272. N3F143 / F205 / P256

- 273. N3F145 / F206 / P257

- 274. N3F147 / F207 / P258

- 275. N3F149 / F208 / P259

- 276. N3F151 / F209 / P260

- 277. N3F151 / P260 verso

- 278. N3F153 / F210 / P261

- 279. N3F155 / F211 / P262

- 280. N3F157 / F212 / P263

- 281. N3F159 / F213 / P264

- 282. N3F161 / F214 / P265

- 283. F161 / P265 verso

- 284. N3F163 / F215 / P266

- 285. N3F165 / F216 / P267

- 286. N3F167 / F217 / P268

- 287. N3F169 / N218 / P269

- 288. N3F170 / P269 verso

- 289. N3F171 / F219 / P270

- 290. N3F173 / F220 / P271

- 291. N3F175 / F221 / P272

- 292. N3F177 / F222 / P273

- 293. N3F179 / F223 / P274

- 294. N3F181 / F224 / P275

- 295. N3F183 / F225 / P276

- 296. N3F185 / F226 / P277

- 297. N3F187 / F227 / P278

- 298. N3F189 / F228 / P279

- 299. N3F191 / F229 / P280

- 300. N3F193 / F230 / P281

- 301. N3F195 / F231 / P282

- 302. N3F197 / F202 / P283

- 303. N3F199 / F203 / P284

- 304. N3F201 / P285

- 305. N5F203 / F205 / P286

- 306. N3F205 / F206 / P287

- 307. N3F207 / F207 / P288

- 308. N3F209 / F208 / P289

- 309. N3F211 / F209 / P290

- 310. N3F213 / F210 / P291

- 311. N3F215 / F211 / P292

- 312. N3F217 / F212 / P293

- 313. N3F219 / F213 / P294

- 314. N3F221 / F214 / P295

- 315. N3F223 / F215 / P296

- 316. N3F225 / F216 / P297

- 317. N3F227 / F217 / P298

- 318. N3F229 / F218 / P299

- 319. N3F231 / F219 / P300

- 320. N3F233 / F220 / P301

- 321. N3F235 / F221 / P302

- 322. N3F237 / F222 / P303

- 323. N3F239 / F223 / P304

- 324. N3F241 / F224 / P305

- 325. N3F243 / F225 / P306

- 326. N3F245 / F226 / P307

- 327. N3F245 / P307 verso

- 328. N3F247 / F227 / P308

- 329. N3F249 / F228 / P309

- 330. N3F251 / F229 / P310

- 331. N3F253 / F230 / P311

- 332. N3F255 / F232 / P312

- 333. N3F257 / F233 / P313

- 334. N3F249 / F234 / P314

- 335. N3F251 / F235 / P315

- 336. N3F253 / F236 / P316

- 337. N3F255 / F237 / P317

- 338. N3F257 / F238 / P318

- 339. N3F259 / F239 / P319

- 340. N3F261 / F240 / P320

- 341. N3F263 / F241 / P321

- 342. N3F265 / F242 / P322

- 343. N3F267 / F243 / P323

- 344. F267 / P323 verso

- 345. N3F269 / F244 / P324

- 346. N3F271 / F245 / P325

- 347. N3F273 / F246 / P326

- 348. N3F275 / F247 / P327

- 349. N3F275 / P327 verso

- 350. N3F277 / F248 / P328

- 351. N3F279 / F249 / P329

- 352. N3F281 / F250 / P330

- 353. N3F283 / F251 / P331

- 354. N3F285 / F251 / P332

- 355. N3F287 / F252 / P333

- 356. N3F289 / F253 / P334

- 357. N3F291 / F254 / P335

- 358. N3F241 / P335 verso

- 359. N3F293 / F255 / Appendix C.336

- 360. N3F295 / F256 / P337

- 361. N3F297 / F257 / P338

- 362. N3F299 / F258 / P339

- 363. N3F301 / F258 / P340

- 364. N3F303 / F259 / P341

- 365. N3F305 / F260 / P342

- 366. N3F307 / F261 / P343

- 367. N3F309 / F262 / P344

- 368. N3F309 /P344 verso

- 369. N3F311 / F263 / P345

- 370. N3F313 / F264 / P346

- 371. N3F315 / F265 / P347

- 372. N3F317 / F266 / P348

- 373. N3F319 / F267 / P349

- 374. N3F321 / F268 / P350

- 375. N3F323 / F269 / P351

- 376. N3F325 / F270 / P352

- 377. N3F271 / P353

- 378. N3F327 / F1 / P354

- 379. N3F329 /P355

- 380. N3F331 / P356

- 381. N3F333 / P357

- 382. N3F335 / P358

- 383. N3F337 / P359

- 384. N3F339 / P360

- 385. N3F253 / verso Berg pg 339

- 386. N3F341 / P361

- 387. N3F343 / P362

- 388. N3F345 / P363

- 389. N3F347 / P364

- 390. N3F349 / P365

- 391. N3F351 / P366

- 392. Appendix A/7

- 393. Appendix A/8

- 394. Appendix A/9

- 395. Appendix A/10

- 396. Appendix A/11

- 397. Appendix A/12

- 398. Appendix A/13

- 399. C/41

- 400. C/42

- 401. C/43

- 402. C/44

- 403. C/156 verso

- 404. C/157 verso

- 405. C/336

- 406. Appendix B

- 407. Albatross Agreement

- 408. DIAL advert