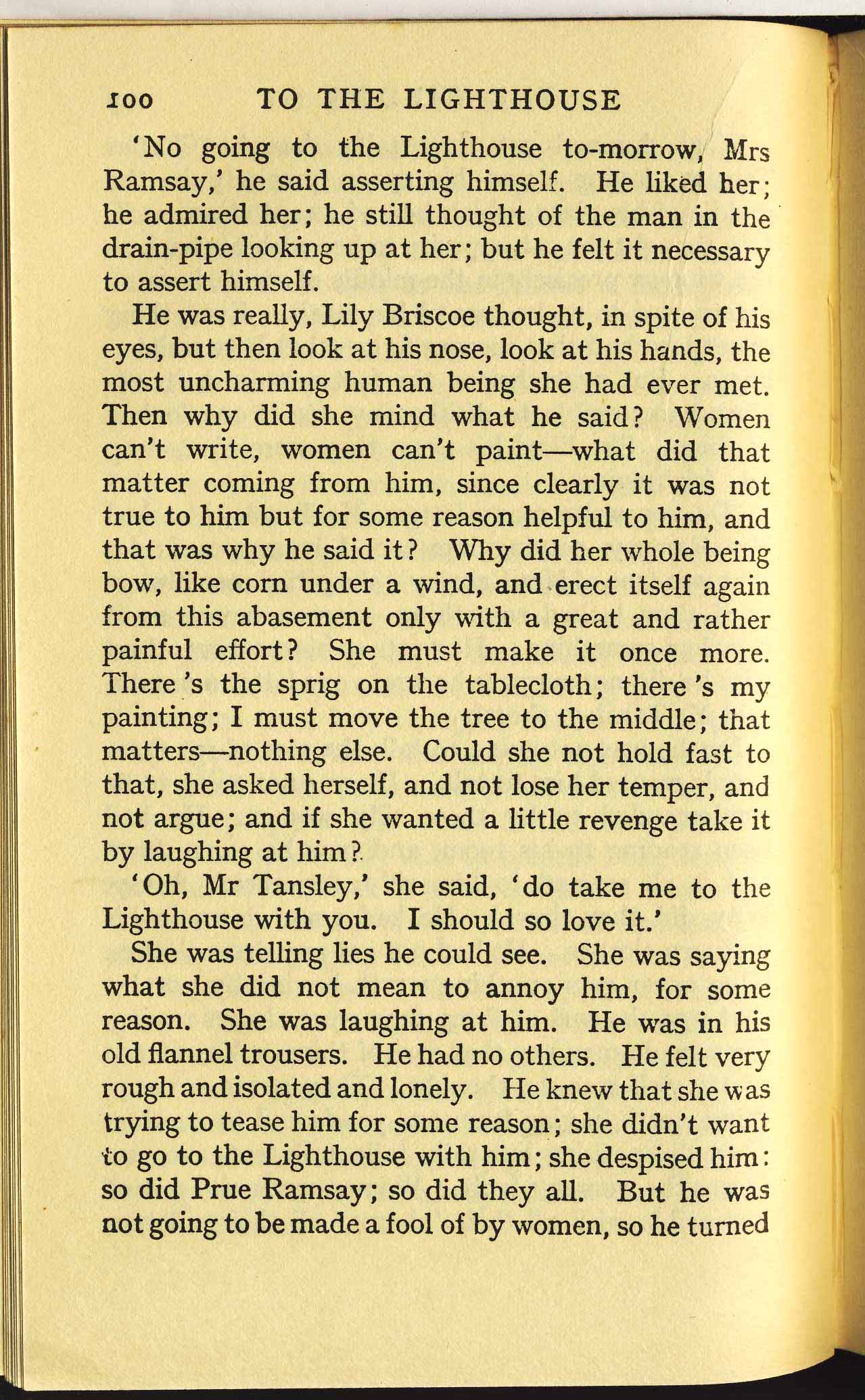

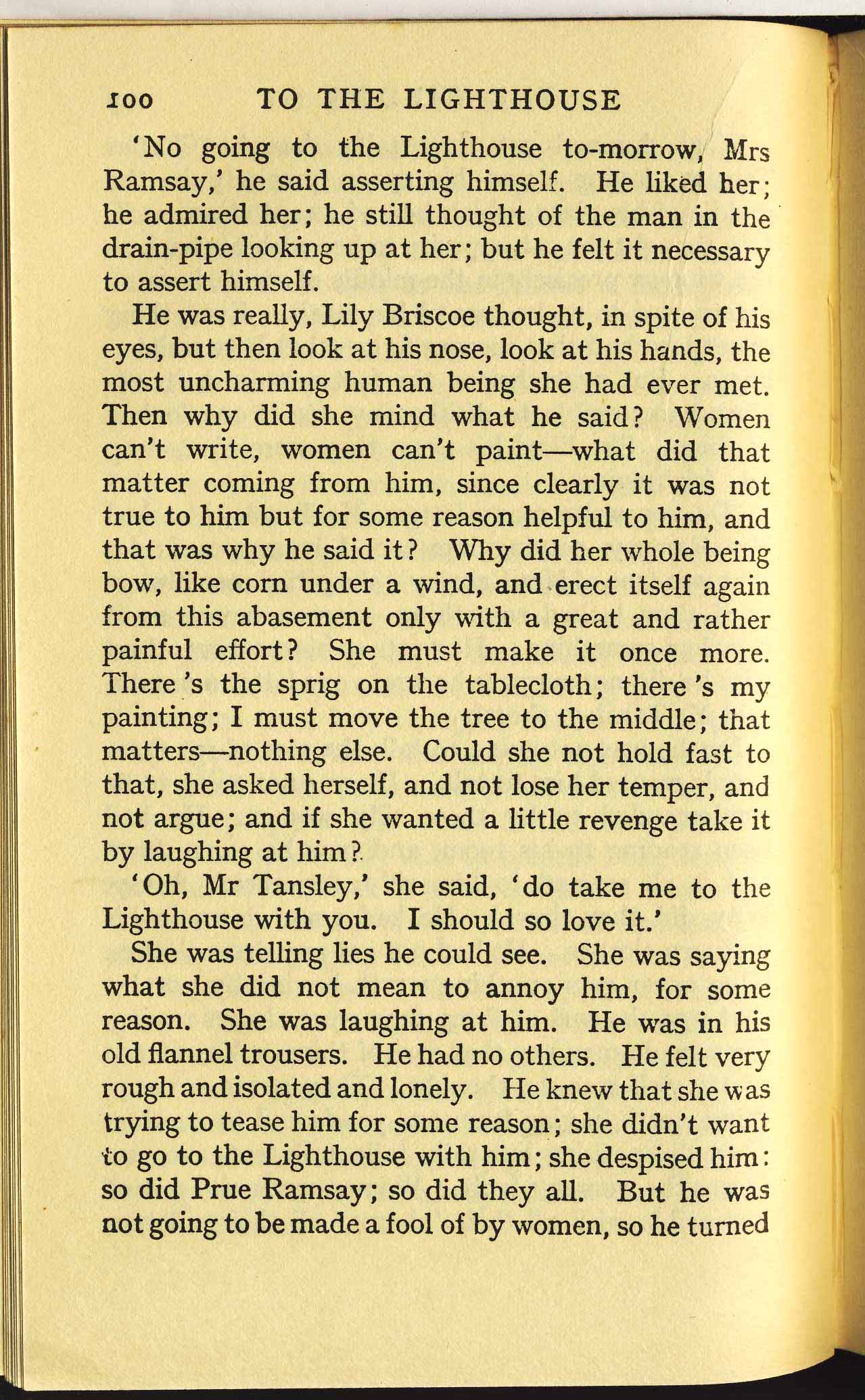

He was really, Lily Briscoe thought, in spite of hiseyes, but then look at his nose, look at his hands, themost uncharming human being she had ever met.Then why did she mind what he said? WomencanŌĆÖt write, women canŌĆÖt paintŌĆöwhat did thatmatter coming from him, since clearly it was nottrue to him but for some reason helpful to him, andthat was why he said it? Why did her whole beingbow, like corn under a wind, and erect itself againfrom this abasement only with a great and ratherpainful effort? She must make it once more.ThereŌĆÖs the sprig on the tablecloth; there's mypainting; I must move the tree to the middle; thatmattersŌĆönothing else. Could she not hold fast tothat, she asked herself, and not lose her temper, andnot argue; and if she wanted a little revenge take itby laughing at him?

ŌĆśOh, Mr Tansley,' she said, ŌĆśdo take me to theLighthouse with you. I should so love it.'She was telling lies he could see. She was sayingwhat she did not mean to annoy him, for somereason. She was laughing at him. He was in hisold flannel trousers. He had no others. He felt veryrough and isolated and lonely. He knew that she wastrying to tease him for some reason; she didn't wantto go to the Lighthouse with him; she despised him:so did Prue Ramsay; so did they all. But he wasnot going to be made a fool of by women, so he turned

Select Pane

Berg Materials

- 1. Notebook I Cover

- 2. F3 / P1

- 3. F5 / P2

- 4. F7 / P3

- 5. F9 / P4

- 6. F11 / P5

- 7. F13 / P6

- 8. F15 / P7

- 9. F17 / P8

- 10. F19 / P9

- 11. F21 / P10

- 12. F23 / P11

- 13. F25 / P12

- 14. verso of Berg F25

- 15. F27 / P13

- 16. F29 / P14

- 17. F31; P15

- 18. F33 / P16

- 19. F35 / P17

- 20. F37 / P18

- 21. F39 / P19

- 22. F41 / P20

- 23. F43 / P21

- 24. F45 / P22

- 25. F47 / P23

- 26. F49 / P24

- 27. F51 / P25

- 28. F53 / P26

- 29. F55 / P27

- 30. F57 / P28

- 31. F59 / P29

- 32. F61 / P30

- 33. F61 / P30 verso

- 34. F63 / P31

- 35. F65 / P32

- 36. F67 / P33

- 37. F69 / P34

- 38. F71 / P35

- 39. verso F71

- 40. F73 / P36

- 41. F75 / P37

- 42. F77 / P38

- 43. F79 / P39

- 44. F81 / P40

- 45. F91 / P45

- 46. F93 / P46

- 47. F95 / P47

- 48. F97 / P48

- 49. F99 / P49

- 50. F101 / P50

- 51. F103 / P51

- 52. F105 / P52

- 53. F107 / P53

- 54. F109 / P54

- 55. F111 / P55

- 56. F113 / P56

- 57. F115 / P57

- 58. F117 / P58

- 59. F119 / P59

- 60. verso F119

- 61. F121 / P60

- 62. F123 / P61

- 63. F125 / P62

- 64. F127 / P63

- 65. F129 / P64

- 66. F131 / P65

- 67. F133 / P66

- 68. F135 / P67

- 69. F137 / P68

- 70. F139 / P69

- 71. F139 / P69 verso

- 72. F141 / P70

- 73. F143 / P71

- 74. F145 / P72

- 75. F147 / P73

- 76. Fol. 149 / P74

- 77. F151 / P75

- 78. F153 / P76

- 79. F155 / P77

- 80. F157 / P78

- 81. F159 / P79

- 82. F161 / P80

- 83. F163 / P81

- 84. F167 / P82

- 85. 167 / P82 verso

- 86. F169 / P83

- 87. F171 / P84

- 88. F173 / P85

- 89. F175 / P86

- 90. F177 / P87

- 91. F179 / P88

- 92. F181 / P89

- 93. F183 / P90

- 94. F185 / P91

- 95. F187 / P92

- 96. F189 / P93

- 97. F191 / P94

- 98. F193 / P95

- 99. F195 / P96

- 100. F197 / P97

- 101. F197 / P97 verso

- 102. F199 / P98

- 103. F199 / P98 verso

- 104. F201 / P99

- 105. F203 / P100

- 106. F205 / P101

- 107. F207 / P102

- 108. F207 / 102 verso

- 109. F209 / P103

- 110. F211 / P104

- 111. F213 / P105

- 112. F215 / P106

- 113. F217 / P107

- 114. F219 / P108

- 115. F221 / P109

- 116. F223 / P110

- 117. F225 / P111

- 118. F227 / P112

- 119. F229 / P113

- 120. F231 / P114

- 121. F233 / P115

- 122. F235 / P116

- 123. F237 / P117

- 124. F239 / P118

- 125. F241 / P119

- 126. F243 / P120

- 127. F245 / P121

- 128. F247 / P122

- 129. F249 / P123

- 130. F251 / P124

- 131. F251 / P124 verso

- 132. F253 / P125

- 133. F255 / P126

- 134. F257 / P127

- 135. F259 / P128

- 136. F261 / P129

- 137. F263 / P130

- 138. F265 / P131

- 139. F267 / P132

- 140. F269 / P133

- 141. F271 / P134

- 142. F273 / P135

- 143. F275 / P136

- 144. F277 / P137

- 145. F279 / P138

- 146. F281 / P139

- 147. F283 / P140

- 148. F285 / P141

- 149. F287 / P142

- 150. F289 / P143

- 151. F291 / P144

- 152. F293 / P145

- 153. F295 / P146

- 154. F297 / P147

- 155. F299 / P148

- 156. F301 / P149

- 157. F303 / P150

- 158. F305 / P151

- 159. F307 / P152

- 160. F309 / P153

- 161. F311/ P154

- 162. F313 / P155

- 163. 156 verso

- 164. 157 verso

- 165. 158 verso

- 166. Notebook I Rear Cover

- 167. Notebook II Cover

- 168. N2F1 / P159

- 169. N2F3 / P160

- 170. N2F5 / P161

- 171. N2F7 / P162

- 172. N2F9 / P163

- 173. N2F11 / P164

- 174. N2F13 / P165

- 175. N2F15 / P166

- 176. N2F17 / P167

- 177. N2F19 / P168

- 178. N2F21 / P169

- 179. N2F23 / P170

- 180. N2F25 / P171

- 181. N2F27 /P172

- 182. N2F29 / P173

- 183. N2F31 / P174

- 184. N2F33 / P175

- 185. N2F35 / P176

- 186. N2F37 / P177

- 187. N2F39 / P178

- 188. N2F41 / P179

- 189. N2F43 / P180

- 190. N2F45 / P181

- 191. N2F47 / P182

- 192. N2F49 / P183

- 193. N2F51 / P184

- 194. Notebook II Rear Cover

- 195. Notebook III Cover

- 196. N3F1 / P185

- 197. N3F[3] / F138 / P186

- 198. N3F5 / F139 / P187

- 199. N3F7 / F140 / P188

- 200. N3F9 / F141 / P189

- 201. N3F11 / F142 / P190

- 202. N3F13 / F142 / P191

- 203. N3F15 / F143 / P192

- 204. N3F17 / F144 / P193

- 205. N3F19 / F145 / P194

- 206. N3F21 / F146 / P195

- 207. N3F23 / F147 / P196

- 208. N3F25 / F148 / P197

- 209. N3F27 / F149 / P198

- 210. N3F29 / F150 / P199

- 211. N3F31 / F151 / P200

- 212. N3F33 / F152 / P201

- 213. N3F35 / F153 / P202

- 214. N3F37 / F154 / P203

- 215. N3F39 / F155 / P204

- 216. N3F41 / F156 / P205

- 217. verso of VW P156

- 218. N3F43 / F157 / P206

- 219. N3F45 / F158 / P207

- 220. N3F47 / F159 / P208

- 221. N3F49 / F160 / P209

- 222. N3F51 / F161 / P210

- 223. N3F53 / F162 / P211

- 224. N3F55 / F163 / P212

- 225. N3F57 / F164 / P213

- 226. N3F59 / F165 / P214

- 227. N3F61/ F166 / P215

- 228. N3F63 / F167 / P216

- 229. F63 / P216 verso

- 230. NF65 / F168 / P217

- 231. N3F67 / F169 / P218

- 232. N3F69 / F170 / P219

- 233. 219 verso

- 234. N3F71 / F171 / P220

- 235. N3F73 / F172 / P221

- 236. N3F75 / F173 / P222

- 237. N3F77 / F174 / P223

- 238. N3F79 / F175 / P224

- 239. N3F81 / F176 / P225

- 240. 225 verso

- 241. N3F83 / F177 / P226

- 242. N3F85 / F178 / P227

- 243. N3F87 / F179 / P228

- 244. N3F89 / F180 / P229

- 245. 229 verso

- 246. N3F91 / F181 / P230

- 247. N3F93 / F182 / P231

- 248. N3F95 / F183 / P232

- 249. N3F97 / F184 / P233

- 250. F99 / P234

- 251. N3F101 / F185 / P235

- 252. N3F103 / F186 / P236

- 253. N3F105 / F187 / P237

- 254. N3F107 / F188 / P238

- 255. N3F109 / F189 / P239

- 256. N3F111 / F190 / P240

- 257. N3F113 / F191 / P241

- 258. N3F115 / F192 / P242

- 259. N3F117 / F193 / P243

- 260. N3F119 / F194 / P244

- 261. N3F121 / F195 / P245

- 262. N3F123 / F196 / P246

- 263. N3F125 / F197 / P247

- 264. N3F127 / F198 / P248

- 265. N3F129 / F199 / P249

- 266. N3F131 / F200 / P250

- 267. N3F133 / F202 / P251

- 268. NF135 / F203 / P252

- 269. N3F137 / F204 / P253

- 270. N3F139 / F205 / P254

- 271. N3F141 / F206 / P255

- 272. N3F143 / F205 / P256

- 273. N3F145 / F206 / P257

- 274. N3F147 / F207 / P258

- 275. N3F149 / F208 / P259

- 276. N3F151 / F209 / P260

- 277. N3F151 / P260 verso

- 278. N3F153 / F210 / P261

- 279. N3F155 / F211 / P262

- 280. N3F157 / F212 / P263

- 281. N3F159 / F213 / P264

- 282. N3F161 / F214 / P265

- 283. F161 / P265 verso

- 284. N3F163 / F215 / P266

- 285. N3F165 / F216 / P267

- 286. N3F167 / F217 / P268

- 287. N3F169 / N218 / P269

- 288. N3F170 / P269 verso

- 289. N3F171 / F219 / P270

- 290. N3F173 / F220 / P271

- 291. N3F175 / F221 / P272

- 292. N3F177 / F222 / P273

- 293. N3F179 / F223 / P274

- 294. N3F181 / F224 / P275

- 295. N3F183 / F225 / P276

- 296. N3F185 / F226 / P277

- 297. N3F187 / F227 / P278

- 298. N3F189 / F228 / P279

- 299. N3F191 / F229 / P280

- 300. N3F193 / F230 / P281

- 301. N3F195 / F231 / P282

- 302. N3F197 / F202 / P283

- 303. N3F199 / F203 / P284

- 304. N3F201 / P285

- 305. N5F203 / F205 / P286

- 306. N3F205 / F206 / P287

- 307. N3F207 / F207 / P288

- 308. N3F209 / F208 / P289

- 309. N3F211 / F209 / P290

- 310. N3F213 / F210 / P291

- 311. N3F215 / F211 / P292

- 312. N3F217 / F212 / P293

- 313. N3F219 / F213 / P294

- 314. N3F221 / F214 / P295

- 315. N3F223 / F215 / P296

- 316. N3F225 / F216 / P297

- 317. N3F227 / F217 / P298

- 318. N3F229 / F218 / P299

- 319. N3F231 / F219 / P300

- 320. N3F233 / F220 / P301

- 321. N3F235 / F221 / P302

- 322. N3F237 / F222 / P303

- 323. N3F239 / F223 / P304

- 324. N3F241 / F224 / P305

- 325. N3F243 / F225 / P306

- 326. N3F245 / F226 / P307

- 327. N3F245 / P307 verso

- 328. N3F247 / F227 / P308

- 329. N3F249 / F228 / P309

- 330. N3F251 / F229 / P310

- 331. N3F253 / F230 / P311

- 332. N3F255 / F232 / P312

- 333. N3F257 / F233 / P313

- 334. N3F249 / F234 / P314

- 335. N3F251 / F235 / P315

- 336. N3F253 / F236 / P316

- 337. N3F255 / F237 / P317

- 338. N3F257 / F238 / P318

- 339. N3F259 / F239 / P319

- 340. N3F261 / F240 / P320

- 341. N3F263 / F241 / P321

- 342. N3F265 / F242 / P322

- 343. N3F267 / F243 / P323

- 344. F267 / P323 verso

- 345. N3F269 / F244 / P324

- 346. N3F271 / F245 / P325

- 347. N3F273 / F246 / P326

- 348. N3F275 / F247 / P327

- 349. N3F275 / P327 verso

- 350. N3F277 / F248 / P328

- 351. N3F279 / F249 / P329

- 352. N3F281 / F250 / P330

- 353. N3F283 / F251 / P331

- 354. N3F285 / F251 / P332

- 355. N3F287 / F252 / P333

- 356. N3F289 / F253 / P334

- 357. N3F291 / F254 / P335

- 358. N3F241 / P335 verso

- 359. N3F293 / F255 / Appendix C.336

- 360. N3F295 / F256 / P337

- 361. N3F297 / F257 / P338

- 362. N3F299 / F258 / P339

- 363. N3F301 / F258 / P340

- 364. N3F303 / F259 / P341

- 365. N3F305 / F260 / P342

- 366. N3F307 / F261 / P343

- 367. N3F309 / F262 / P344

- 368. N3F309 /P344 verso

- 369. N3F311 / F263 / P345

- 370. N3F313 / F264 / P346

- 371. N3F315 / F265 / P347

- 372. N3F317 / F266 / P348

- 373. N3F319 / F267 / P349

- 374. N3F321 / F268 / P350

- 375. N3F323 / F269 / P351

- 376. N3F325 / F270 / P352

- 377. N3F271 / P353

- 378. N3F327 / F1 / P354

- 379. N3F329 /P355

- 380. N3F331 / P356

- 381. N3F333 / P357

- 382. N3F335 / P358

- 383. N3F337 / P359

- 384. N3F339 / P360

- 385. N3F253 / verso Berg pg 339

- 386. N3F341 / P361

- 387. N3F343 / P362

- 388. N3F345 / P363

- 389. N3F347 / P364

- 390. N3F349 / P365

- 391. N3F351 / P366

- 392. Appendix A/7

- 393. Appendix A/8

- 394. Appendix A/9

- 395. Appendix A/10

- 396. Appendix A/11

- 397. Appendix A/12

- 398. Appendix A/13

- 399. C/41

- 400. C/42

- 401. C/43

- 402. C/44

- 403. C/156 verso

- 404. C/157 verso

- 405. C/336

- 406. Appendix B

- 407. Albatross Agreement

- 408. DIAL advert