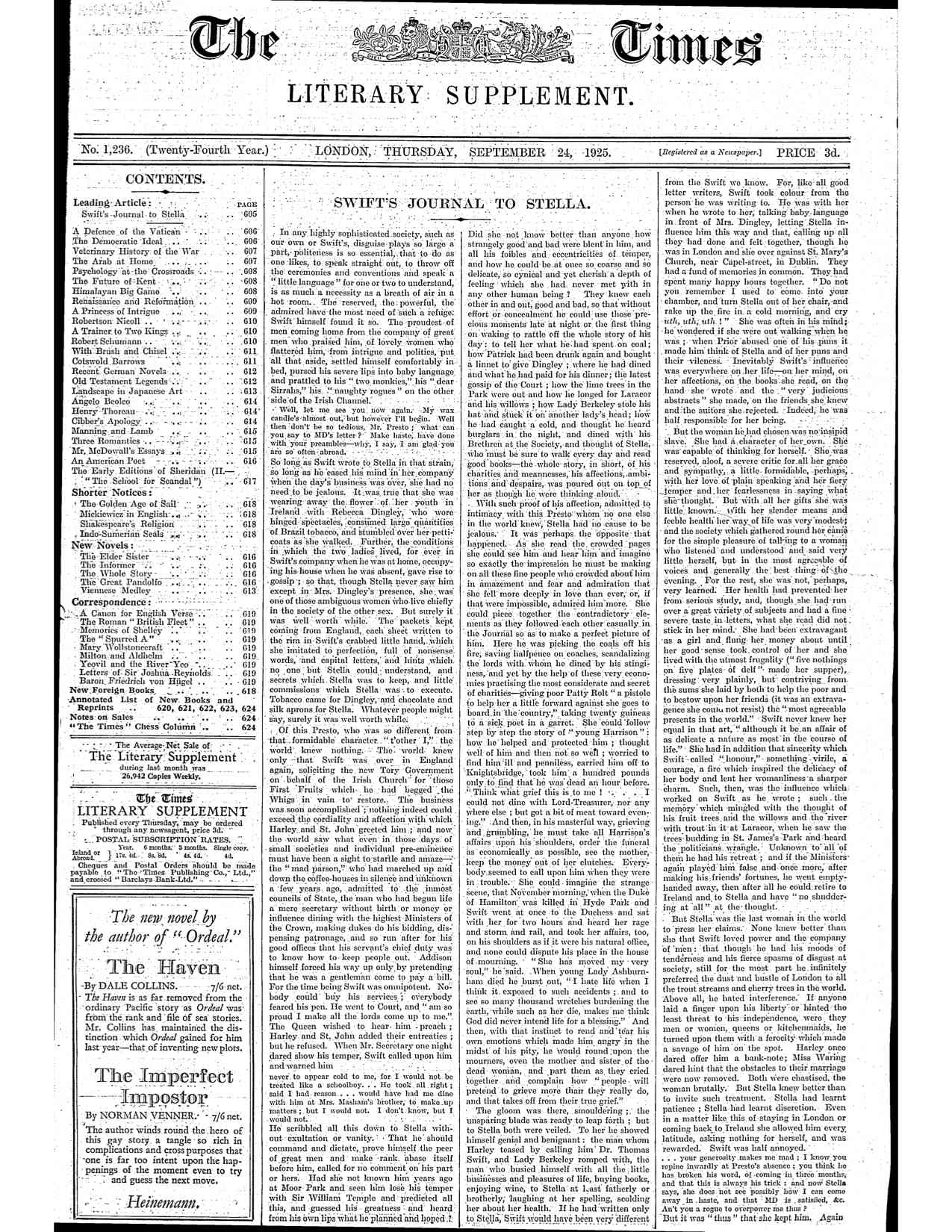

SWIFT’S JOURNAL TO STELLA

In any highly sophisticated society, such as

our own or Swift’s, disguise plays so large a

part, politeness is so essential, that to do as

one likes, to speak straight out, to throw off

the ceremonies and conventions and speak a

“little language” for one or two to understand,

is as much a necessity as a breath of air in a

hot room. The reserved, the powerful, the

admired have the most need of such a refuge.

Swift himself found it so. The proudest of

men coming home from the company of great

men who praised him, of lovely women who

flattered him, from intrigue and politics, put

all that aside, settled himself comfortably in

bed, pursed his severe lips into baby language

and prattled to his “two monkies,” his “dear

Sirrahs,” his “naughty rogues” on the other

side of the Irish Channel.

Well, let me see you now again. My wax

candle’s almost out, but however I’ll begin. Well

then don’t be so tedious, Mr. Presto; what can

you say to MD’s letter? Make haste, have done

with your preambles—why, I say, I am glad you

are so often abroad.

So long as Swift wrote to Stella in that strain,

so long as he eased his mind in her company

when the day’s business was over, she had no

need to be jealous. It was true that she was

wearing away the flower of her youth in

Ireland with Rebecca Dingley, who wore

hinged spectacles, consumed large quantities

of Brazil tobacco, and stumbled over her petti-

coats as she walked. Further, the conditions

in which the two ladies lived, for ever in

Swift’s company when he was at home, occupy-

ing his house when he was absent, gave rise to

gossip; so that, though Stella never saw him

except in Mrs. Dingley’s presence, she was

one of those ambiguous women who live chiefly

in the society of the other sex. But surely it

was well worth while. The packets kept

coming from England, each sheet written to

the rim in Swift’s crabbed little hand, which

she imitated to perfection, full of nonsense

words, and capital letters, and hints which

no one but Stella could understand, and

secrets which Stella was to keep, and little

commissions which Stella was to execute.

Tobacco came for Dingley, and chocolate and

silk aprons for Stella. Whatever people might

say, surely it was well worth while.

Of this Presto, who was so different from

that formidable character “t’other I,” the

world knew nothing. The world knew

only that Swift was over in England

again, soliciting the new Tory Government

on behalf of the Irish Church for those

First Fruits which he had begged the

Whigs in vain to restore. The business

was soon accomplished; nothing indeed could

exceed the cordiality and affection with which

Harley and St. John greeted him; and now

the world saw what even in those days of

small societies and individual pre-eminence

must have been a sight to startle and amaze—

the “mad parson,” who had marched up and

down the coffee-houses in silence and unknown

a few years ago, admitted to the inmost

councils of State, the man who had begun life

a mere secretary without birth or money or

influence dining with the highest Ministers of

the Crown, making dukes do his bidding, dis-

pensing patronage, and so run after for his

good offices that his servant’s chief duty was

to know how to keep people out. Addison

himself forced his way up only by pretending

that he was a gentleman come to pay a bill.

For the time being Swift was omnipotent. No-

body could buy his services; everybody

feared his pen. He went to Court, and “am so

proud I make all the lords come up to me.”

The Queen wished to hear him preach;

Harley and St. John added their entreaties;

but he refused. When Mr. Secretary one night

dared show his temper, Swift called upon him

and warned him

never to appear cold to me, for I would not be

treated like a schoolboy… He took all right;

said I had reason… would have had me dine

with him at Mrs. Masham’s brother, to make up

matters; but I would not. I don’t know, but I

would not.

He scribbled all this down to Stella without exultation or vanity. That he should

command and dictate, prove himself the peer

of great men and make rank abase itself

before him, called for no comment on his part

or hers. Had she not known him years ago

at Moor Park and seen him lose his temper

with Sir William Temple and predicted all

this, and guessed his greatness and heard

from his own lips what he planned and hoped?

[new column]

Did she not know better than anyone how

strangely good and bad were blent in him, and

all his foibles and eccentricities of temper,

and how he could be at once so coarse and so

delicate, so cynical and yet cherish a depth of

feeling which she had never met with in

any other human being? They knew each

other in and out, good and bad, so that without

effort or concealment he could use those pre-

cious moments late at night or the first thing

on waking to rattle off the whole story of his

day: to tell her what he had spent on coal;

how Patrick had been drunk again and bought

a linnet to give Dingley; where he had dined

and what he had paid for his dinner; the latest

gossip of the Court; how the lime trees in the

Park were out and how he longed for Laracor

and his willows; how Lady Berkeley stole his

hat and stuck it on another lady’s head; how

he had caught a cold, and thought he heard

burglars in the night, and dined with his

Brethren at the Society, and thought of Stella,

who must be sure to walk every day and read

good books—the whole story, in short, of his

charities and meannesses, his affections, ambi-

tions and despairs, was poured out on top of

her as though he were thinking aloud.

With such proof of his affection, admitted to

intimacy with this Presto whom no one else

in the world knew, Stella had no cause to be

jealous. It was perhaps the opposite that

happened. As she read the crowded pages

she could see him and hear him and imagine

so exactly the impression he must be making

on all these fine people who crowded about him

in amazement and fear and admiration that

she fell more deeply in love than ever, or, if

that were impossible, admired him more. She

could piece together the contradictory ele-

ments as they followed each other casually in

the Journal so as to make a perfect picture of

him. Here he was picking the coals off his

fire, saving halfpence on coaches, scandalizing

the lords with whom he dined by his sting-

iness, and yet by the help of those very econo-

mies practising the most considerate and secret

of charities—giving poor Patty Rolt “a pistole

to help her a little forward against she goes to

board in the country,” taking twenty guineas

to a sick poet in a garret. She could follow

step by step the story of “young Harrison”:

how he helped and protected him; thought

well of him and then not so well; worried to

find him ill and penniless, carried him off to

Knightsbridge, took him a hundred pounds

only to find that he was dead an hour before.

“Think what grief this is to me! . . . I

could not dine with Lord-Treasurer, nor any

where else; but got a bit of meat toward even-

ing.” And then, in his masterful way, grieving

and grumbling, he must take all Harrison’s

affairs upon his shoulders, order the funeral

as economically as possible, see the mother,

keep the money out of her clutches. Every-

body seemed to call upon him when they were

in trouble. She could imagine the strange

scene, that November morning, when the Duke

of Hamilton was killed in Hyde Park and

Swift went at once to the Duchess and sat

with her for two hours and heard her rage

and storm and rail, and took her affairs, too,

on his shoulders as if it were his natural office,

and none could dispute his place in the house

of mourning. “She has moved my very

soul,” he said. When young Lady Ashburn-

ham died he burst out, “I hate life when I

think it exposed to such accidents; and to

see so many thousand wretches burdening the

earth, while such as her die, makes me think

God did never intend life for a blessing.” And

then, with that instinct to rend and tear his

own emotions which made him angry in the

midst of his pity, he would round upon the

mourners, even the mother and sister of the

dead woman, and part them as they cried

together and complain how “people will

pretend to grieve more than they really do,

and that takes off from their true grief.”

The gloom was there, smouldering; the

unsparing blade was ready to leap forth; but

to Stella both were veiled. To her he showed

himself genial and benignant: the man whom

Harley teased by calling him Dr. Thomas

Swift, and Lady Berkeley romped with, the

man who busied himself with all the little

businesses and pleasures of life, buying books,

enjoying wine, to Stella at least fatherly or

brotherly, laughing at her spelling, scolding

her about her health. If he had written only

to Stella, Swift would have been very different

[new column]

from the Swift we know. For, like all good

letter writers, Swift took colour from the

person he was writing to. He was with her

when he wrote to her, talking baby language

in front of Mrs. Dingley, letting Stella in-

fluence him this way and that, calling up all

they had done and felt together, though he

was in London and she over against St. Mary’s

Church, near Capel-street, in Dublin. They

had a fund of memories in common. They had

spent many happy hours together. “Do not

you remember I used to come into your

chamber, and turn Stella out of her chair, and

rake up the fire in a cold morning, and cry

uth, uth, uth!” She was often in his mind;

he wondered if she were out walking when he

was; when Prior abused one of his puns it

made him think of Stella and of her puns and

their vileness. Inevitably Swift’s influence

was everywhere on her life—on her mind, on

her affections, on the books she read, on the

hand she wrote and the “very judicious

abstracts” she made, on the friends she knew

and the suitors she rejected. Indeed, he was

half responsible for her being.

But the woman he had chosen was no insipid

slave. She had a character of her own. She

was capable of thinking for herself. She was

reserved, aloof, a severe critic for all her grace

and sympathy, a little formidable, perhaps,

with her love of plain speaking and her fiery

temper and her fearlessness in saying what

she thought. But with all her gifts she was

little known. With her slender means and

feeble health her way of life was very modest;

and the society which gathered round her came

for the simple pleasure of talking to a woman

who listened and understood and said very

little herself, but in the most agreeable of

voices and generally the best thing of the

evening. For the rest, she was not, perhaps,

very learned. Her health had prevented her

from serious study, and, though she had run

over a great variety of subjects and had a fine

severe taste in letters, what she read did not

stick in her mind. She had been extravagant

as a girl and flung her money about until

her good sense took control of her and she

lived with the utmost frugality (“five nothings

on five plates of delf” made her supper),

dressing very plainly, but contriving from

the sums she laid by both to help the poor and

to bestow upon her friends (it was an extrava-

gence she could not resist) the “most agreeable

presents in the world.” Swift never knew her

equal in that art, “although it be an affair of

as delicate a nature as most in the course of

life.” She had in addition that sincerity which

Swift called “honour,” something virile, a

courage, a fire which inspired the delicacy of

her body and lent her womanliness a sharper

charm. Such, then, was the influence which

worked on Swift as he wrote; such the

memory which mingled with the thought of

his fruit trees and the willows and the river

with trout in it at Laracor, when he saw the

trees budding in St. James’s Park and heard

the politicians wrangle. Unknown to all of

them he had his retreat; and if the Ministers

again played him false and once more, after

making his friends’ fortunes, he went empty-

handed away, then after all he could retire to

Ireland and to Stella and have “no shudder-

ing at all” at the thought.

But Stella was the last woman in the world

to press her claims. None knew better than

she that Swift loved power and the company

of men: that though he had his moods of

tenderness and his fierce spasms of disgust at

society, still for the most part he infinitely

preferred the dust and bustle of London to all

the trout streams and cherry trees in the world.

Above all, he hated interference. If anyone

laid a finger upon his liberty or hinted the

least threat to his independence, were they

men or women, queens or kitchenmaids, he

turned upon them with a ferocity which made

a savage of him on the spot. Harley once

dared offer him a bank-note; Miss Waring

dared hint that the obstacles to their marriage

were now removed. Both were chastised, the

woman brutally. But Stella knew better than

to invite such treatment. Stella had learnt

patience; Stella had learnt discretion. Even

in a matter like this of staying in London or

coming back to Ireland she allowed him every

latitude, asking nothing for herself, and was

rewarded. Swift was half annoyed.

…your generosity makes me mad; I know you

repine inwardly at Presto’s absence; you think he

has broken his word, of coming in three months,

and that this is always his trick: and now Stella

says, she does not see possibly how I can come

away in haste, and that MD is satisfied, &c.

An’t you a rogue to overpower me thus?

But it was “thus” that she kept him. Again